Identifying fin rot

Fin rot is a general term for necrotic loss of fin tissue, resulting in split or ragged fins. It is usually the edge of the fin that is attacked, although occasionally a hole may appear in the middle of the fin. The appearance of fin rot can vary between a distinct, semi-circular “bite” shape and a “shredded” effect.

The edge of the lesion is usually opaque or whitish. In advanced cases there may be some reddening or inflammation. The main threat from this fish disease is, if left untreated fin rot can slowly eat away the entire fin along with the fin rays and start to invade the fish’s body, leading to peduncle disease if the caudal (tail) fin is involved, or saddleback ulcer if the dorsal (top) fin is affected. Fin rot is a bacterial disease involving opportunistic bacteria such as Aeromonas, Pseudomonas or Flexibacter that abound in all aquatic environments. Secondary fungal infections are not uncommon.

Fin Rot (necrotic ulceration of fins) |

|

A severe infection of the caudal fin of a koi. There is extensive inflammation around the lesion extending into the body of the fish. This fish recovered and surprisingly the fin did partially re-grow, with the two halves knitting back together |

|

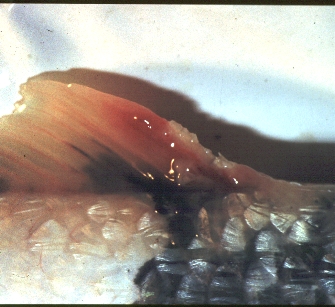

Typical fin rot affecting the dorsal fin of a koi. On the leading edge of the lesion is an area of white necrotic tissue. Surrounding this is a large area of inflamed, infected tissue. The front fin ray has been exposed and destroyed. The infection has reached the fish’s body |

|

A extreme example of fin rot of the caudal fin. The white necrotic region of the fin edge is clearly visible. The whole of the fin is very red and inflamed. The infection has entered the body of the fish resulting in raised scales and a large area of inflammation. A extreme example of fin rot of the caudal fin. The white necrotic region of the fin edge is clearly visible. The whole of the fin is very red and inflamed. The infection has entered the body of the fish resulting in raised scales and a large area of inflammation. |

|

|

All of these fish recovered following fin trimming, topical treatment and a course of antibiotics. The fish in the top picture had his fin stitched. It held for a day or two, which was long enough for the healing process to start. It was either that or remove it! |

|

|

photos: Frank Prince-Iles |

|

Usually caused by stress

With very few exceptions, virtually all cases are precipitated by stress, fear or poor environmental conditions. Indeed, fin rot is often one of the first signs that a fish disease problem exists and all cases should be investigated to determine the underlying cause. When I have fish in for hospitalization, occasionally some sensitive fish will start to develop fin rot as a consequence of their strange new surroundings and being handled – even though they are being kept in optimum conditions. It is usually self-resolving as they settle in, but does demonstrate just how sensitive fish can be to stress and how fin erosion is often a sign that all is not well.

Treatment

At the expense of being repetitive, stress is the major cause of fin rot. This could be due to a fish disease such as parasites, or overcrowding, low oxygen levels, bullying, poor water quality etc. The most important first step is to resolve any stressors. If caught early, this may be sufficient.

In more advanced cases it may be necessary to trim the affected fin and remove the necrotic tissue. This has to be done when the fish is sedated. It is important to use sterile scissors and treat the clean edge with an antiseptic such as povodine-iodine. This procedure does carry with it a risk of secondary infection and it is important that the fish is returned to optimum conditions and its progress closely monitored for the next week or so.

If the fin rot has advanced the full length of the fin and is threatening the body, this procedure would need to be accompanied by a course of suitable antibiotics.

Does the tissue grow back? In minor cases where only the fin tissue is affected it probably will, but in more advanced cases, particularly if the fin rays (bones) are affected, the chances of re-growth are slim

As antimicrobials for baths go, Tetra Lifeguard is a new, safe Halamid antimicrobial bath. They’ve worked out the safety by mixing the compound with a slow dissolving mineraloid, preventing levels from exceeding 20ppm