A Distressing Condition

Fish gills are susceptible to parasite, bacterial and fungal diseases. Another common condition is hyperplasia, which if not resolved is often fatal. Gill problems are a major cause of fish losses, particularly, it seems, koi. It is a distressing condition to deal with, both for the fish and owner, as too often the disease is at an advanced stage before it becomes obvious that something is wrong. At such a stage there is often little that can be done to save the fish.

To understand why gill disease is such a threat, how it is caused, it is important to have an understanding of the anatomy and function of the gills. This will give us an insight into how conditions such as hyperplasia arise and why parasite and bacterial gill diseases are such a threat. With this understanding we will be better placed to spot early clinical signs that something is amiss and decide how best to treat gill problems.

Gill structure

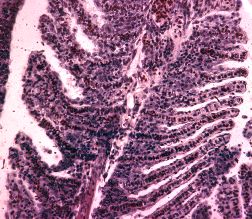

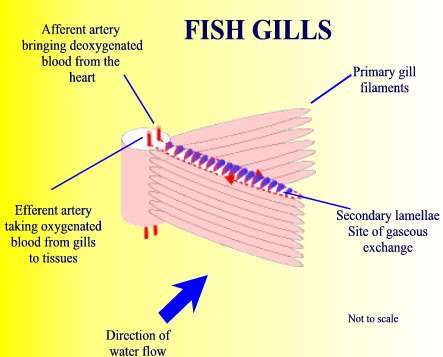

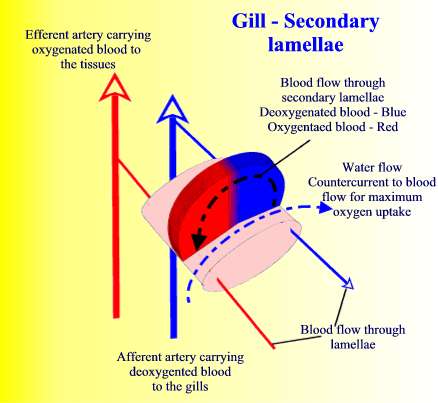

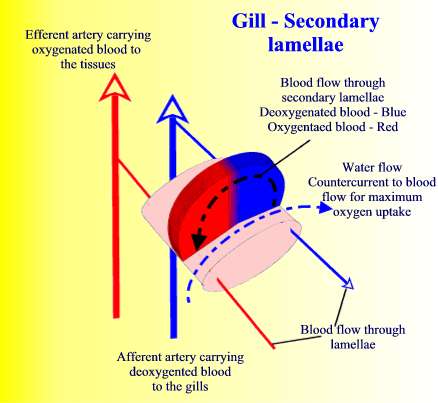

The gills comprise of rows of long, thin primary filaments attached to a gill arch – a bit like the teeth of a comb. This is what you see when you look inside the operculum (gill cover). Running across the primary filament, on both both sides, are a rows of tiny semi-circular foldings – the secondary lamellae.

Fish Gills |

|

|

The delicate and complex structure of fish gills |

|

The secondary lamellae and their role in gaseous exchange |

|

Normal gills at low magnification showing primary gill filaments with the secondary lamellae branching out from each side – the Christmas tree look! The viability of the secondary lamellae is crucial to fish health |

|

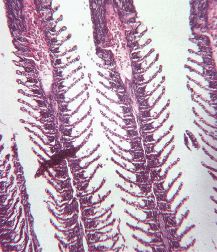

High magnification of healthy gill tissue. The red blood cells pass in a single column through the secondary lamellae where they pick up oxygen and dump carbon dioxide and ammonia. |

|

photos: Frank Prince-Iles |

|

These can be seen in the diagrams and microphotographs above. Deoxygenated blood from the heart is pumped into the primary filaments via the afferent artery. It passes through the secondary lamellae where gaseous exchange takes place – and then back down the efferent artery. The oxygenated blood is then circulated around the body tissues before returning to the heart and starting all over again..

Gaseous exchange – or how fish ‘breath’

Gaseous exchange takes place by diffusion. This is facilitated by the delicate structure of the secondary lamellae. The gill epithelium, (the outer covering, a sort of skin) is extremely thin, usually just one cell thick. Small molecules such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, ammonia etc. can pass through the epithelium – from the water into the blood vessels running immediately under the epithelium – almost as if there wasn’t a barrier.

Anything that interferes with, damages or obstructs this delicate structure is clearly going to be extremely damaging to fish health.

Gill structure and disease

The fish gill has very little protection, other than the bony cover – the operculum – and is susceptible to both physical and chemical damage. A common response of the gill to irritation – whether from parasites, suspended solids or ammonia, or indeed any other irritant – is hyperplasia. Hyperplasia is an abnormal increase in the number of cells in an organ, in this case the gill epithelium. This is similar to calluses that form on hands when subjected to physical work such as digging. Hyperplasia is usually accompanied by increased mucus production.

Gill Hyperplasia |

|

|

|

Hyperplasia; Chemical or physical irritation cause addition cells to grow as a form of protection. Secondary lamellae clump together affecting gaseous exchange and respiration |

|

|

The effects of hyperplasia – higher magnification. Gills are swollen and clumped |

|

Extreme hyperplasia where both the secondary lamellae and primary filaments are clumped together in a mass of tissue. No gaseous exchange can take place and the fish literally suffocates. |

|

photos: Frank Prince-Iles |

|

In addition to hyperplasia, the gill is also susceptible to bacterial and fungal disease as a result of poor water quality, stress or parasites. For this reason most gill disease is really a ‘management disease’ resulting from poor conditions such as;

- chemical irritants such as ammonia and nitrite or high pH

- high levels of parasites such as Trichodina, Chilodonella, Flukes or Costia

- high levels of dissolved or particulate organic solids

- low levels of oxygen or overcrowding

Gill disease diagnosis

The main problem with fish gills is that unlike the rest of the body, we can’t readily see what is happening. Often by the time it becomes obvious that the fish is ill, the damage is advanced and untreatable, so therefore an early diagnosis and treatment is vital.

- The early signs are fish respiring heavily. You can judge this by watching the operculum movements and comparing them to other fish.

- Fish laying on the bottom for long periods – general lethargy – not eating

- Fish tending to use one pectoral fin, keeping the other folded back against the body

- At a more advanced stage you may notice that the fish can’t fully close the operculum because of gill swelling.

- Affected fish may segregate and stay alone – often near the surface or water return

- There may be strands of mucus trailing from the gills

- At a really advanced stage – and usually too late for treatment – the fish will lay on the bottom with its pectoral and dorsal fins clamped to its body – literally waiting to die!

- The other problem in advanced cases is treating against parasites. The combination of excess mucus and hyperplasia forms a secure shelter for any parasites between the secondary lamellae making them very difficult to get at!

Treatments

- Right from the start I should stress that prevention is better than cure and with good water management practices, most gill disease is avoidable.

- If there is the suspicion of a gill problem, is it just one fish or are several affected? The latter will probably indicate an environmental cause.

- Check the water for ammonia, nitrite pH and when was the last time the system was cleaned? If several fish are affected, the system should be cleaned and a substantial water change made, somewhere between 50 -75%. Such is the seriousness of this type of disease.

- In minor cases simply providing optimum environmental conditions may be enough. (Check out the water quality pages and see if you come up to the five point standard); Optimum conditions are mandatory if gill disease is to be successfully treated.

- Examine the fish for parasites. At this stage a skin scrape from immediately behind the operculum will suffice.

- For individual fish a salt bath on two consecutive days is a good start. It won’t exacerbate the problem and will help remove any excess mucus or parasites.

- If the salt treatment fails to work the next stage is probably a gill biopsy to see what is going on. If this shows a parasite problem then these will need to be treated. With regard to treating gill disease, a combination of chloramine-T and benzalkonium as separate treatments in a treatment tank – not the pond – will help resolve gill problems provided that they are not too advanced. See the treatment pages for details.

- Potassium permanganate can be used, but it is often a kill or cure treatment. It will rapidly reduce the parasite and bacterial levels as well as reducing dissolved organics. The draw back is that it will push the really sick fish over the top – mainly I suspect because the permanganate forms a temporary precipitate of manganese dioxide in the gills, affecting fish with severe respiratory problems.

- The outlook for more advanced cases where there is severe hyperplasia and/or bacterial / fungal infection is not good. I have had some success – not a lot – with intensive treatment of chloramine-T and benzalkonium chloride together with antibiotic treatment.